Hirayama observes, and at times captures the world around him. Underneath the imperceptible flow of life, there is an anchor deeper to him that does not allow him to be drifted away like all the others around him..

(spoilers for Perfect Days)

Perfect days(2023) by Wim Wenders is a strange film for its times. There is no inciting incident that will send the protagonist on an adventure, no new knowledge upon which the protagonist must act to save the day, no bombastic climax involving our hero facing off the villian. There are small incidents, and negligible reactions to them, a steady stream of wisdom that is hard to catch, and seemingly unexciting days that require no saving. The films quietens the world around, as if to bring attention to the gentle pulsebeat of the wrist, barely noticed, yet which is the very sign of life like no other.

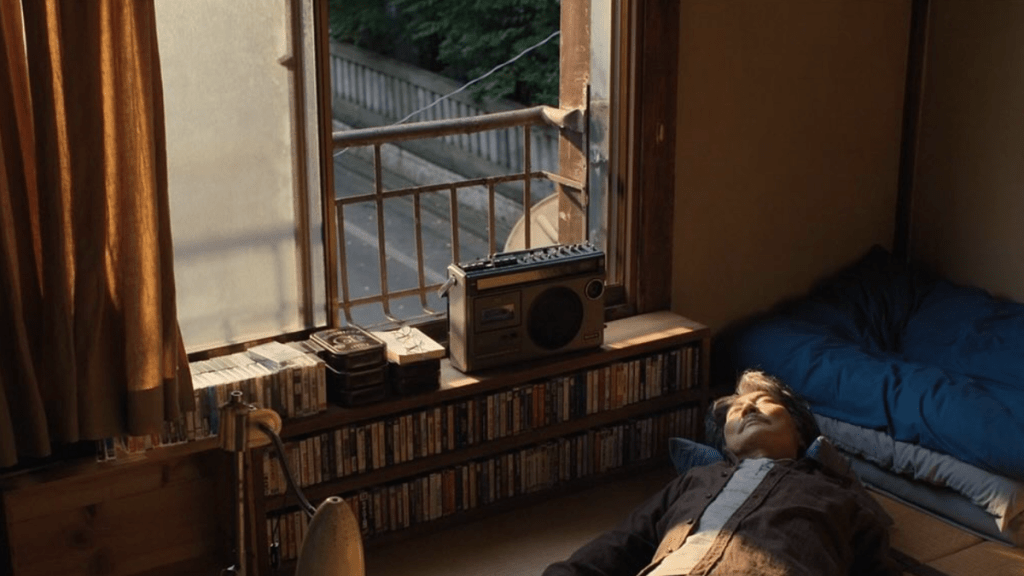

In the center of the film is Hirayama. Working as a toilet cleaner in Tokyo. His routine is simple: water the plants at pre-dawn, get ready for work, have coffee from a dispenser, commute, clean toilets spick-and-span, have a sandwich under a tree in the park–capture it through an old Olympus film camera– back to work, public bathroom, an evening at a diner where the person serving him declares ‘for your hard work’, back to home, read at night, go to sleep. Sundays are about laundry, lunch at a favorite junction, buying a new book, and cycling around the city. Any deviation in his routine is brought by the mischiefs of his colleagues or the daily hassles of life, rather than by his own volition. He barely talks; like, barely. It is not social anxiety, or the hesitance of indulging in the world that might snap back at the slightest gesture. He just doesn’t talk.

He is content with his life, enjoys his days, carries grief and pain too, yet in a way is at peace with the frayed edges of his life. His niece, Niko, seemed to catch on this too, and enjoys this very aspect of his company. In a beautiful shot, standing alongside the river bank with the setting sun in front of them, both on cycles, Niko wishes to go to the seaside with him. Hirayama promises her some other day and on further questioning by Niko, says ‘next time is next time, now is now’. When his wealthy estranged sister comes to retrieve Niko, in a quiet scene of minimal dialogues, she asks him, with a hesitant repulsion in her voice: ‘do you really clean toilets?’. His reaction is a proud nod: yes!

Hirayama observes, and at times captures the world around him. It does not seem that people are living alongside him as much as they are living around him. The flowing of their everyday lives brush against his own. Yet he carries a certain weight no one else around him do. Underneath the imperceptible flow of life, there is an anchor deeper to him that does not allow him to be drifted away like all the others around him. Like the trees he captures, there is a stillness to him that defies stagnancy.

There is a goal, even a necessity to never provide a sense of connection in an Other. Instead, it is made to be found throughout the world.

There is a moment where Hirayama finds a game of tic-tac-toe on a piece of paper behind a toilet stall, and commences a game with the unknown person throughout the film who we will never see.

It is there that I was reminded of Death Stranding, a 2021 video game by Hideo Kojima, about a solitary protagonist Sam Porter Bridges in a post apocalyptic America where he has to deliver supplies to cities and ports at the other ends of a desecrated continent. The world is riddled with a strange phenomenon called ‘timefall’, a type of hallucinatory otherworldly rain that accelerates the flow of time and ages any living or non living thing that is unluckily caught in its spell. Humanity is on the brink of extinction, divided, and in desperate need of connection with one another, both on a metaphorical level, and on the practical level of exchanging important supplies across the continent. Since the terrains are uneven and at times barbarous, the primary mode of traversal is walking great distances. Both the film and the game involve a relatively mute protagonist at the center. Both involve quotidian tasks of cleaning and walking respectively. Both the film and game touch on similar themes. While Hirayama sees before him the glimmer of sunlight behind trees, for Sam it is the vast vistas of grasslands and snowcapped mountains in the distant, and both alone in their journeys of navigating them. Their quotidian labor forces them to come in reckoning with the beauty and simplicity around them. Hirayama puts in a cassette while driving to work, Death Stranding introduced the slow swelling of music during its cutscene-esque gameplay.

Death Stranding’s gameplay is unique, such the fact that it involves asynchronous multiplayer. Normal multiplayer games involve two players at the other side of the server, joining the main server and playing against or with each other, at the same time. In Death Stranding, no two players ever interact with each other, and are only made aware of each others presence through the items (like ropes, ladders, bridges built, cars, etc) that they leave behind, since objects left behind in your world can appear in other worlds. There is a mechanism in the game where you can call out at the empty world, and if any other player is present in their vicinity, it will trigger a response from them. The moment is hauntingly beautiful. At best you can describe it as a spectre of another player’s tracks, emanating in their brief presence and whatever links they have left behind. It’s as if Kojima were to say: ‘you are alone in your struggles, but not in the journey’.

Many films and stories talk about the struggle of two characters who are separate or separated from each other, and must overcome the hurdles to come together at last. There common themes are about finding oneness in each other’s physical presence, and any form of separateness is death-like. The sense of connection is embodied in the ‘Other’, and one must get to this Other to fulfil that sense of connection. Yet, Death Stranding and Perfect Days, by never showing who is on the other side, emphasize on a larger sense of connectedness. By denying the sense of connectedness in a definable and comprehensible Other, it challenges us to find it within everything around us that remains ignored in our rush to find it in the concrete, measurable Others. The spiritualists would call it ‘the oneness of existence’: the idea that each and every entity is linked to each other to create a larger whole, and their is a unity in their existence that transcends physical barriers.

We never meet who is on the other end of the tic-tac-toe game. We never meet the other player in Death Stranding. Yet I argue that there is a certain goal, even a necessity to never provide this ‘connection’ in the end. Since, what cannot be denied, is that there was someone on the other end, and that that shared moment, however brief, is a part of common history to both of them. It is their crossing of paths rather than meeting of those paths that remain at the forefront here. The sense of connectedness is emphasised over the connection. The means never conclude to an end because the means were always more than sufficient in themselves.