In life, Franz Kafka didn’t achieve what he did in death; to give a name to any meaningless existence that puts up question marks one after the other, refusing to cease into a definite conclusion. His works have often been said to have a ‘nightmarish’ quality in them. A nightmare that is a direct result of uncertainty, and where everything becomes a convoluted mess. The only solution to this complication is to end the nightmare, but to end the nightmare itself- the complication needs to be resolved.

Frederick R. Karl, the author of Kafka’s monumental biography, stated Kafkaesque as-

-when you enter a surreal world in which all your control patterns, all your plans, the whole way in which you have configured your own behaviour, begins to fall to pieces when you find yourself against a force that does not lend itself to the way you perceive the world. You don’t give up, you don’t lie down and die. What you do is to struggle against this with all of your equipment, with whatever you have. But of course, you don’t stand a chance

Kafka’s characters struggle with all their might against an immovable omnipotent force that exhausts all their inventory while still not budging an inch. Karl described it as “the forces that wait malevolently for the human endeavour to falter.”

It is a force so strong, it could easily break a human apart. The nightmare lies in the fact that it simply doesn’t do so, or simply the protagonist never gives in. It might be the case that Kafka never conceptualised this force as ‘malevolent’, or even a form of ‘force’ in any way. It is less of an antagonistic force and more of a way of being; an existing system. It is not the paragon of evil or the perpetrator of Orwellian laws. It does not do what it does to establish tyranny; in fact, even the system itself is unaware of the damage it causes.

It does so because this is how it behaves: like a curious child putting its fingers in paths of unaware ants, observing their tormented state as they move in circles. Even if by some chance, the ant questions the intent of the child, the child would find no semblance of commonality between this insignificant creature and itself, no notion of the power it possesses, no contemplation on the consequence of his action. The child would simply squash the ant without hesitation. A whole existence trampled as nonchalantly as a court magistrate signing Josef K.’s arrest warrant. The only momentary attention given to check for his nonexistent surname.

Kafka could never villainize his antagonists. Nor did he make the antagonist familiar enough to be understood.

The motif of an oppressive and unintelligible system prevails in almost all of Kafka’s work but especially in his best piece ‘The Trial’. Kafka could never villainize his antagonists. Nor did he make the antagonist familiar enough to be understood. They remained distant from the action while simultaneously affecting it. It is their natural way of being, the natural way of their internal working- that the protagonist, only to happen to get involved in, accepts it, and struggles endlessly against it. The oppressive forces aren’t active in the true sense. Their oppression doesn’t lie in the fact that they willingly oppress, but in the fact that they force a rigid sandbox on an incongruent subject who doesn’t question this swift change but simply accepts it with great anguish.

The deepest state of horror in Kafka’s writing lies in the fact that the protagonist doesn’t stay aware of this hurt inflicted on him through this extraordinary situation. He adapts to it, as if it was meant to be this way in the first place. The resultant helplessness causes a disparity between the protagonist’s decision to accept this baselessly agonising situation- and the reader’s unease at the protagonist’s decision itself. Gregor, expecting life to go on as it should after the horrendous incident that he went through is the anchor of absurdity here, not that Gregor turned into a bug. Josef’s acceptance of the trial against him that has absolutely no basis whatsoever is the humanistic absurdity that Kafka touched on here, not the presence of an incomprehensible legal system that accuses people without any evidence.

An arbitrary grave injustice inflicted becomes a foundation for reconciliation is the most terrifying aspect here.

Each obstacle overcome brings not with it a sense of achievement, but a foreshadowing of the agony that is yet to come. The past accomplishments look pale in comparison. It further accentuates the meaninglessness of your action, yet never letting you fall- since to let you fall is to end the struggle.

An arbitrary grave injustice inflicted becomes a foundation for reconciliation is the most terrifying aspect here. And terrifying more so because it is the pinnacle vice of an abusive relationship based on mismatched power dynamics; as in the case of the relationship between Franz and his father Hermann Kafka.

Hermann is typically described as a tyrannical abusive father. Although this is the general opinion that he is described by- the umbrella statement does not do justice to the nuances of Franz’s derogatory relationship with his father and how it did actually shape him. Kafka did, after all, express firsthand his gratitude and respect for his father and restraint to express his unfiltered hate. The apologetic timidness in the opening of his lengthy ‘Letter to Father’ wherein he expressed the lifelong anguish that he had to suffer through due to his father’s inconsistent and frigid nature, is the prime example of how Kafka is unable to acknowledge to even himself, any form of genuine ill feelings based on objectively ill-actions by his father. Every torment that his father inflicted on him has been watered down by himself as an unknowing action on his part. He simply diffuses the acquisitions as “The effect you had on me was the effect you could not help having”.

Nor could Kafka at his young age, understand the double standards that his father had set up as to who would be wrong or right- which solely depended on who the doer was. And even if the blame was to be taken by Hermann, it was taken by his son, in regards to the authority-follower relationship that they had. His built-up angst is diluted by crumbs of love that his father would show only seldom.

Kafka knew somewhere that hurt is being inflicted but the exact nature of hurt itself is obscure and unimaginable; leading to the belief that the hurt was meaningless to begin with. All the anxiety that was built is redirected towards the self in the form of shame and doubt. Even if animosity did develop, it would implode rather than explode.

A conflation in love and anger can and will understandably cause dissonance in Kafka’s opinion about his father’s behaviour. There are in general two options that a child can proceed with forward in life; correlate affection with aggression and express anger as a form of love, or, be completely disoriented by this dichotomous behaviour- constantly finding cracks and faults in his own perceptions and never really settling with any of them.

Kafka might have been better off if he was an idiot..

In that sense, Kafka might have been better off if he was an idiot; or he had gotten a complete monster for a father. For a monster, as degenerate, as it may be, would’ve nullified the dichotomy. Kafka would have resented the monster without any opposing thought or any reflection on the anger. There would be no friction of contradictory statements and firm decisions could’ve been taken. But Kafka could not do that. If he would have been stupid, he would have; and it would be easy to convince him that his father was not the paragon of virtue but in fact, a deeply flawed individual whose moral ground itself is fragile.

Sadly, that letter never reached his father since he could never pluck up the courage to hand the letter to him directly, nor could his mother do the same. That letter remained in Kafka’s possession until his death.

It took me a lot of time to think about the ending for this essay than it did for me to write down the essay itself, or even come up with the title. Many aspects of Kafka’s life are still untouched here, his relationships (especially with Felice Bauer), his warm and friendly nature for which he was considered very calm and approachable, and the humour in his writing, which by the way is immense and ever-present (thankfully, David Foster Wallace has covered this in his essay ‘Laughing with Kafka’). Keeping in mind Kafka’s underwhelming writing career, his unresolved relationship with his father and his contempt for himself and even for his own craft: I decided to not conclude the article in its whole, and let the bare open threads that beg for their ends to be met, to remain as they are- hanging loose in empty space. Perhaps this is an inappropriate metaphor, unfit and making no sense. If that is so, then it couldn’t be better. It is Franz Kafka’s life after all. A life without a conclusion.

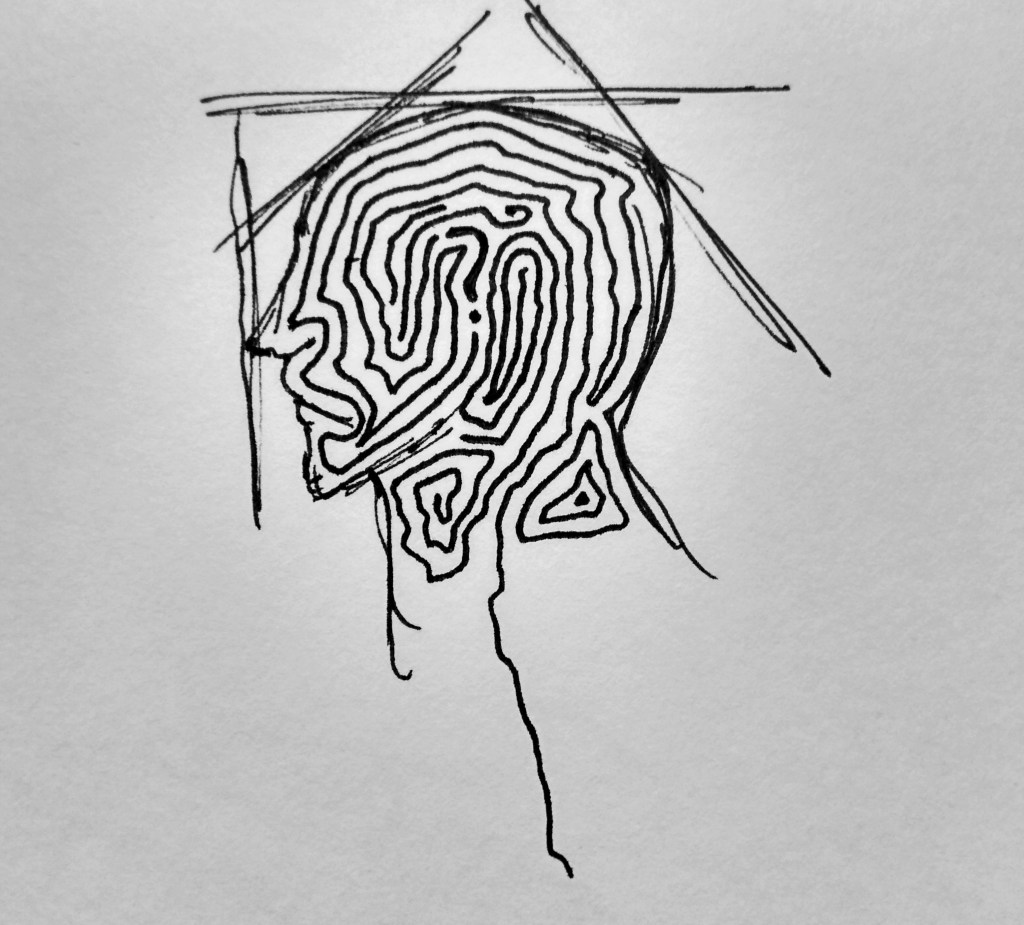

*All the uncredited artwork is produced by the author himself.*

Reblogged this on Abyss.

LikeLike